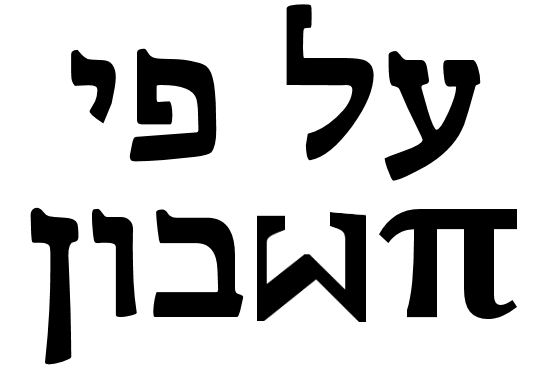

Goats and Amicable Numbers

In this week’s parasha, we find Yaakov preparing for his encounter with his twin brother Esav in several ways. Among other preparations, Yaakov sends him gifts consisting of various different kinds of animals. The Torah tells us (Bereishit 32:14–16) how many of each kind of animal Yaakov sent: 200 female goats and 20 male goats; 200 female sheep (ewes) and 20 male sheep (rams); 30 nursing camels with their young; 40 female cows and 10 bulls; 20 female donkeys and 10 male donkeys. What is the significance of these numbers?

In his ספר בעלי ברית אברם, R’ Avraham Azulai provides an explanation for the number of goats, which he attributes to R’ Nachshon Gaon of the 9th century. The total number of goats is 200 + 20 = 220. What significant property does the number 220 have?

Consider the factors of 220, that is, numbers that multiply together to give the product 220. We can factor the number 220 in the following ways:

220 = 1 × 220

220 = 2 × 110

220 = 4 × 55

220 = 5 × 44

220 = 10 × 22

220 = 11 × 20

Now consider only the “proper factors” of 220 – that is, all the factors in the above list, excluding the number 220 itself – and add them up:

1 + 2 + 4 + 5 + 10 + 11 + 20 + 22 + 44 + 55 + 110 = 284

So the proper factors of 220 add up to 284.

We now repeat the process, considering the factors of 284. We can factor the number 284 in the following ways:

284 = 1 × 284

284 = 2 × 142

284 = 4 × 71

Again, we consider only the proper factors of 284 – all the factors in the above list, excluding the number 284 itself – and add them up:

1 + 2 + 4 + 71 + 142 = 220

So the proper factors of 284 add up to 220. Does this number look familiar?

As we have just shown, the numbers 220 and 284 have the property that the proper factors of each number add up to the other number. A pair of numbers with this property is known as a pair of amicable numbers, or according to R’ Nachshon Gaon, מנין נאהב. Apparently it was known to the ancients that in order to gain the love of kings and princes, a person would give one of a pair of amicable numbers as a present, keeping the other number for himself. This is so that the factors of the number given add up to the number kept, and the factors of the number kept add up to the number given. So this is what Yaakov did. He sent Esav 220 goats, and kept 284 for himself.

Wait a minute: The Torah tells us that Yaakov gave Esav 220 goats, but where do we see in the Torah that he kept 284 for himself? Several pesukim later, as Yaakov gives instructions to the servants carrying the gifts, the Torah records (32:21), “כי־אמר אכפרה פניו במנחה ההולכת לפני” – “for he said: I will win him over with the gifts that are being sent ahead.” R’ Nachshon Gaon explains that this sentence contains a hint to the number 284, in the following way. The word אכפרה can be divided in two parts: אכ פרה. When the Torah uses the word אך, it is generally interpreted by the Rabbis to indicate exclusion or reduction. Calculating the numerical value of the second part of the word, פרה, we get: 80 (פ) + 200 (ר) + 5 (ה) = 285. Applying a reduction (indicated by אך) to the value 285 (given by פרה), we obtain a value of 284. This represents the number of goats that Yaakov kept for himself, according to R’ Nachshon Gaon.

Special thanks to Daniel Levenstein for bringing this insight to my attention.

Addendum: Yaakov sent a number of different types of animals. Why were only goats sent in amicable numbers? See an interesting thought from רבנו בחיי which may shed some light on this question.

References:

Leonard Eugene Dickson, History of the Theory of Numbers, Volume I: Divisibility and Primality, Carnegie Institute of Washington: Washington, 1919, p. 39, available at:

http://www.archive.org/stream/historyoftheoryo01dick#page/38/

ר' אברהם ב"ר מרדכי אזולאי, ספר בעלי ברית אברם, published 1873 but existed in manuscript for 300 years previously; pp. 48–49, available beginning at:

http://www.hebrewbooks.org/pdfpager.aspx?req=3997&pgnum=47

הנאהבים והנעימים - על רעות אצל מספרים, in Michlalah Jerusalem College's mathematical journal אלף אפס (ℵ₀):

http://alefefes.macam.ac.il/article/article.asp?n=15

(may not work in all browsers)

(Thanks to Yaaqov Loewinger for this link via Hebrew Wikipedia)

Friday, December 13, 2024

Wednesday, October 16, 2024

How many בקשות in יעלה ויבוא

Since we are about to say יעלה ויבוא numerous times (perhaps as many as 40 times) I figured it would be a good time to explore this:

Wow, 347 בקשות packed into one small תפילה!

A friend once approached with an interesting project - to calculate the total number of בקשות in יעלה ויבוא. Now, of course, that's not as simple as it seems. It is not simple addition. It involves a lot of multiplication.

So let's dive into it:

| יעלה | ויבוא | ויגיע | ויראה | וירצה | וישמע | ויפקד | ויזכר | = 8 |

| (Keep in mind that all the above verbs will apply to all of the following nouns:) | |

| זכרוננו | ופקדוננו | וזיכרון אבותינו | וזיכרון משיח בן דוד עבדך | וזיכרון ירושלים עיר קדשך | וזיכרון כל עמך בית ישראל | x 6 |

| = 48 | |

| (And then the following modify all of the above:) | |

| |לפניך לפליטה | לטובה | לחן | ולחסד | ולרחמים | לחיים ולשלום | x 7 |

| So the entire first section | = 336 |

| זכרנו ה' אלוקינו בו לטובה | ופקדנו בו לברכה | והושיענו בו לחיים טובים | + 3 |

| = 339 | |

| Now we add the final portion: | |

| ובדבר ישועה | ורחמים | = 2 |

| חוס | וחננו | ורחם עלינו | והושיענו | x 4 |

| = 8 | |

| So the final count is 339 + 8 | = 347 |

Wow, 347 בקשות packed into one small תפילה!

Labels:

תפילה

Thursday, September 19, 2024

Balancing the Shevatim at Har Grizim and Har Eival

In the fall of 1992, there was a fascinating article concerning this week's parsha written up in Tradition magazine by Rabbi Michael Broyde of Atlanta and Steven Weiner of Los Angeles. I will try to sum up the article as concisely as possible. The pasuk tells us (27:12-13) that the tribes of Shimon, Levi, Yehuda, Yissachar, Yosef and Binyamin stood on Har Grizim for the delivering of the beracha. Reuven, Gad, Asher, Zevulun, Dan and Naftali stood on Har Eival for the delivering of the kelala. The gemara (Sotah 37a) presents a quandary based on a pasuk in Yehoshua that seems to show that the kohanim were in the middle of the two mountains. So how could they be said to have been on Har Grizim? The gemara gives three different answers as to how the kohanim were split up, some below, and some on the mountain (according to two of the answers.) The answer that seems to be most dealt with amongst the meforshim is that those who were 'fit for work' were below with the aron, and those who were not were above. Rashi learns this to refer to those above thirty while the Maharsh"a learns that it is referring to b'nei Kehas who were in charge of the aron.

Now, in dividing the tribes between two mountains, there are 462 different ways to make such a division [12! / 2(6!6!)]. Broyde and Weiner point out a fascinating fact. Taking the most recent census data that we are given in the Torah and dealing with the answer of the gemara that we have discussed, if you examine every single possible formation of the tribes, the actual formation of the tribes is the absolute most even division of the tribes possible. That is, the difference in population between the two mountains is at a minimum with this formation. [I personally wrote a computer program to test it out and it worked. In the article, they include a list of all possible combinations and their respective differences.] What is even more fascinating, is that this works out for both Rashi and the Maharsh"a. And what may be the most fascinating of all is that according to the Maharsh"a, the population on Har Grizim would have been 307,929 and that of Har Eival 307,930. No, that's not a typo. That is a difference of 1! According to both, this is by far the most even division of the tribes.

The next step is what to do with such an impressive observation. What does this tell us? I will leave that for the reader to decide. [In the article, they suggest a parallel to that which we are taught (Kiddushin 40b) that one should always look at the world as if it were half righteous and half guilty and the judgement of the entire world is dependent on him.] But for what it's worth, it is surely an intriguing observation on its own.

The article became the subject of debate in the Spring of 1999 with The Solution to Deuteronomy is not in Numbers, a rebuttal by Sheldon Epstein, Yonah Wilamowsky & Bernard Dickman. This was then followed up by A Mathematical Solution on Terra Firma and a Geographical Explanation on Weak Ground by the original authors.

IMPORTANT UPDATE: Tradition magazine has been gracious enough to make their archives fully available to the public! So following the links above will now allow you to read the articles in their entirety.

IMPORTANT UPDATE: Tradition magazine has been gracious enough to make their archives fully available to the public! So following the links above will now allow you to read the articles in their entirety.

Friday, August 2, 2024

Splitting up the Animals

Some time after the victorious military campaign against Midyan, ל"א:כ"ה-מ"ז, all of the booty - humans and animals - is counted and divided in two. One half is designated for the soldiers who fought the war and the other half is for the rest of בני ישראל. Of the half that went to the soldiers, one out of 500 was to be given to אלעזר. Of the half that went to the rest of the nation, one out of 50 was given to the לויים.

There are a number of puzzling nuances in this chapter. First the totals of the sheep, cattle, donkeys and humans are tallied. Then the halves to the soldiers are counted as well as אלעזר's portion. The halves to the rest of the nation, although exactly the same as the halves to the soldiers are counted. It is recounted that משה distributed the portion for the לויים but no count is given. Lastly, אלעזר's portion is said to be "from the humans, from the cattle, from the donkeys and from the sheep." The same phrase is repeated with regards to the portion of the לויים but the words מכל הבהמה, from all of the animals, is added.

נצי"ב, in העמק דבר, suggests that מכל הבהמה includes other species of animals that were brought back that were fewer in number. Since they were fewer than 1000, there would not have been enough to give אלעזר even one. Therefore, this phrase is left out of the command of אלעזר's portion and these animals' numbers are not significant enough for the תורה to recount.

A fascinating approach is offered in the name of ר' שלמה הכהן מווילנא. Elazar's portion is referred to in פסוק כ"ט as a 'תרומה לה. One of the laws of תרומה is that one may not separate from one species as תרומה for another. Therefore, אלעזר's portion was required to be one out of every 500 of each animal. However, this was not a requirement with the portion of the לויים and it was sufficient to give them 1/50 of all the animals combined. That is the meaning of מכל הבהמה. The לויים were given 1/50 of all the animals. And that is why the תורה does not go into any detail concerning the division for it was not exact.

Friday, July 26, 2024

The Probability of the Goral

In pasuk 26:54, the Torah explains how the land was divided amongst the tribes. Rashi explains exactly how the lots were picked to determine each tribe's portion.

Even though the portions were Divinely predetermined, a lot-drawing process was used to assign each tribe their portion. Rashi explains that one drum was filled with 24 pieces of paper. On 12 pieces of paper were written the names of the 12 tribes. On the other 12 were written the 12 portions that were to be assigned to the tribes. Each Nasi approached the drum and picked out two pieces of paper. One paper had the name of his tribe written on it and the other the prescribed portion of land in Eretz Yisrael. The purpose of this exercise was to prove the Divinity of division plan that allotted each tribe its portion and appease any tribe who felt it might be unfair. As such, I believe that a miracle of this type may be more greatly appreciated if we knew exactly how unlikely it would have been to happen naturally.

Suppose we had a prescribed list of which portion was to be assigned to which tribe. What would be the odds of each Nasi picking out both the name of his tribe and also the corresponding piece of land that had already been prescribed? Let us start with the first Nasi. He has 24 pieces of paper to choose from. He must pick two specific pieces of paper out of the drum. The odds of taking the first one correctly would be 1/24 and then the odds of taking the second correctly would be 1/23. However, since the two papers were taken together, the order does not matter. The rules of probability theory state that if the order of the choices is not relevant, than the odds must be multiplied by the number of possible sequences which, in this case, is two. So the odds of the first Nasi picking the right pieces is 2/(24 x 23). With 22 pieces of paper remaining, the odds of the second Nasi picking correctly will be 2/(22 x 21). And so on. The last Nasi's odds will be 2/(2 x 1) which is 1. That means that he will definitely pick the right ones. That is understandable. By the rules of probability theory, in order to find the odds of all the Nesiim picking correctly, we must multiply each Nasi's odds together. Thus, the odds may be generalized as

| 212 |

| (24 x 23 x 22 x 21...x 2 x 1) |

24 x 23 x 22 x 21....x 2 x 1 is referred to as 24 factorial and expressed as 24! Thus the final expression is 212/24!. When all is totalled, the odds of the draw falling out exactly as planned without any Divine intervention would have been one in 151,476,000,000,000,000,000.

This calculation is based on Rashi's explanation in the chumash according to the Midrash Tanchuma. However, Rashi (actually written by Rashbam, Rashi's grandson,) in the gemara (Bava Basra 122a) states clearly that two drums were used. This will alter the calculation somewhat. The first Nasi would have a 1/12 chance of picking his tribe's name from the tribe drum and a 1/12 chance of picking the correct portion from the portion drum. The fact that the order does not matter will not affect the odds in this case because the choices are made from two separate groups. The odds for both drums are multiplied and thus, the first Nasi's odds will be 1/122. The odds of the second Nasi will be 1/112. And so on. The total odds will be:

| 1 |

| 122 x 112 x 102 x 92 x 82 x 72 x 62 x 52 x 42 x 32 x 22 x 12 |

This can, in fact, be simplified as 1/12!2. The final odds will be one in 229,442,532,802,560,000. This is approximately 660 times more probable than the odds according to Rashi on the chumash.

Just to get an idea of the extent of this improbability, the odds of winning the Powerball Jackpot are approximately one in 175 million. That is over 1.3 billion times more likely to happen than this, according to Rashi on the gemara, and over 860 billion times more likely according to Rashi on the chumash. The odds of getting fatally hit by lightning in a given year are approximately 1 in 2.4 million. In fact, it is more likely for one to win the Powerball twice in one week or get fatally hit by lightning two-and-a-half times in one year than for the goral's results to have been produced naturally. This is a veritable testimony to the extent of the miracle that occurred and the Divinity of the apportioning of Eretz Yisroel to the twelve tribes.

תשע"ד: A similar drawing came up this week in דף יומי on :תענית כ"ז regarding the גורל used to determine the order of the משמרות in the בית שני. According to רש"י's understanding, there was a similar miracle at play. The probability associated with that drawing is discussed here.

תשע"ד: A similar drawing came up this week in דף יומי on :תענית כ"ז regarding the גורל used to determine the order of the משמרות in the בית שני. According to רש"י's understanding, there was a similar miracle at play. The probability associated with that drawing is discussed here.

Labels:

Probability,

פינחס,

פרשה

Friday, July 19, 2024

Counting the Judges

In the end of Parshas Balak, (pasuk 25:5), Moshe passes on HaShem's command to carry out justice upon those who worshipped Ba'al Pe'or.

Rashi states that there were 88,000 "Dayanei Yisroel" and cites the gemara at the end of the first perek of Sanhedrin. However, the gemara over there clearly calculates the number of Dayanei Yisroel to be 78,6001. Of course the obvious easy way out would be to say that there is an error in our version of Rashi, which would require only the replacing of the word shemonas with the word shiv'as to get close enough to the true number. This, in fact, seems to be the version of Rashi that the Ramban had. However, whenever this is avoidable it is best not to rely on such an answer and to justify our reading of Rashi. But is it avoidable in this instance?

Perhaps, it is possible that Rashi is not referring to the actual number given in Sanhedrin but to the calculation done there. Just as when B'nei Yisroel were 603,550 the number of dayanim was 78,600 the number of dayanim based on B'nei Yisroel's current population would be around 88,000. The next step, then, is to calculate what population would require 88,000 dayanim. Being that the dayanim included judges of groups of 1000, 100, 50 and 10 the following equation is given:

| 88,000 | = (x/1000) + (x/100) + (x/50) + (x/10) (where x = total population) |

| = (100x + 20x + 10x + x)/1000 (multiplying by 1000/1000, i.e. 1) | |

| = 131x/1000 (131 judges per 1000 citizens) | |

| x | = 88,000,000/131 |

| x | = 671,755 (rounded down) |

A population of close to 672,000 is needed to necessitate 88,000 dayanim. This is an odd number since none of the recorded censuses rendered a number anywhere near this. But as clearly shown in the very Rashi in question, there was to be a large population decrease before B'nei Yisroel would reach the figure of 601,730 given in Pinchas. To justify this figure of 671,755 we must account for 70,000 lost lives. The only definite casualty count we are given is the 24,000 who perished in the plague following the worship of Ba'al Pe'or. That still leaves 46,00 lives unaccounted for. Starting from Beha'aloscha there were a number of catastrophic incidents recorded in which many fell from B'nei B'nei Yisroel. However, many of these may not be considered in this particular calculation. If B'nei Yisroel did in fact reach a population as large as we are suggesting then it must have happened gradually from the time of the census in Bemidbar to the time that they began their decline to the figure given in Pinchas. Therefore, since the individual plagues from Beha'aloscha to Korach were still in the second year and, for the most part, immediately after the census in Bemidbar we may not consider them in the decline of the population toward the figure of 601,730.

We are left, then, with only three incidents to consider. The first is the episode following the death of Aharon when B'nei Yisroel began to return toward Mitzrayim and B'nei Levi ran after them (see Rashi 26:13). The Yerushalmi records that only eight (or seven, see Rashi and the Yerushalmi inside) families were wiped out from Yisroel in that incident. This would seem to represent a significant loss but perhaps not 46,000.

The second is the episode with the snakes (Bemidbar 21) where, as recorded in the Mishna (Rosh HaShanah 29a), those who were bitten and did not have appropriate kavana when shown the copper snake perished. Here, too, there is no significant loss recorded but only that proper kavana was required for the snake to cure you. Before the cure, however, the pasuk states (pasuk 6) that a great multitude perished from Yisroel. We are not given any further information, though, on the number of casualties2.

Finally, there is the plague of Ba'al Pe'or. That leads into a discussion as to what in fact transpired besides the loss of 24,000 in the plague. From the fact that the Torah refers to a magefa, it is doubtful that this refers to those killed by the shoftim. So how many people did the shoftim kill? The Ramban (on this pasuk) quotes a Yerushalmi, the simple reading of which implies that each shofet killed two men as commanded by Moshe. This would render well over 150,000 casualties. Ramban, however, concludes that the figure given by the Yerushalmi is just referring to how many would have been killed had Moshe's command been carried out but in the end the shoftim never had a chance to do so and they didn't kill a soul. Perhaps it is possible to take this idea of the Ramban that the shoftim were interrupted before having a chance to complete their mission, but to suggest that they had already begun to carry it out when they were interrupted. With or without such a supposition, one could suggest that in some way, these three incidents combined for a grand total of 46,000 fatalities. The other 24,000 died in the magefa. Now we have accounted for all 70,000 lives and all the figures work out.

Nevertheless, it is doubtful that Rashi actually wrote 88,000 and had this convoluted calculation in mind. Rather, it is more reasonable to assume that this version of Rashi is a mistake and that he originally wrote 78,000, particularly because the Ramban had such a reading of Rashi. However, I am not the first to try and justify the figure of 88,000. The Margaliyos HaYam on the gemara in Sanhedrin cites the sefer Techeles Mordechai who offers a calculation based on a population of 603,550:

| 603 | shoftim over a thousand |

| 6,035 | shoftim over a hundred |

| 12,071 | shoftim over fifty |

| 60,355 | shoftim over ten |

| 70 | zekeinim |

| 276 | (12x23 small Sanhedrin for each tribe) |

| 72 | (12x6 Nesi'im for each tribe) |

| 8,580 | Levi'im |

| =88,002 |

There are a number of details involved in this figure that may be questionable. Firstly, we have previously determined that before the sin of Ba'al Pe'or the population was at least 625,000. Also, there is no source that indicates that all these different parties were included in the term "Dayanei Yisroel." The gemara in Sanhedrin certainly did not include them. Then Rashi's comment on this pasuk would have absolutely nothing to do with the gemara and from the text of Rashi it seems that Rashi himself cited the gemara in Sanhedrin. So, the conclusion remains that the proper reading of Rashi is most likely 78,000 rather than 88,000.

1Although it is not the subject of this piece, it is interesting to note the various discussions concerning the calculation in Sanhedrin. The Yad Ramah and one opinion in Tosafos state that the shoftim were all over 60 and were not part of the general population. Another opinion in Tosafos states that the shoftim of 50 were taken from the shoftim of ten, the shoftim of 100 were taken from the shoftim of 50, etc. This, however, is not in accordance with the Yerushalmi quoted here by the Ramban. See also Margaliyos HaYam who raises a number of interesting questions regarding the figure given there. It bothered me, though, that the calculation is based on 600,000 not 603,550 which would render a different total.

2The Zohar in Parshas Balak cites an opinion that this pasuk is referring to Tzelafchad alone for he was the leader of his tribe (Source: Ta'ma D'Kra, R' Chaim Kunyevsky)

Friday, May 17, 2024

Omer Counting in Different Bases

My father-in-law showed me a ספר that discusses whether or not you can fulfill your obligation to count the עומר using other base systems besides decimal. This a good case where the question is far more interesting than the answer. Surely, one should not do that. However, it was a very interesting concept I had never thought of before. So, I added a widget on the blog's sidebar which will display the day of the Omer in various relevant bases.

On the insistence of reader Pi (that's his shorter name), I have added base 7 as well as a pick-your-own-base section.

Here is the excerpt from the ספר.

Labels:

ספירת העומר

Thursday, March 14, 2024

Happy π Day

We wish you all a happy Pi Day, today being March 14th which, in the US anyway, is expressed as 3-14. Pi day was first observed in the year 1593. Ok, I'm just making that up (and rounding.) Just to give this some semblance of a Torah flavour, here is our post on Pi in the Torah

In European countries where the day is written before the month, Pi Day is observed on April 31. For information on that, you would have needed to contact me this past Sunday morning at 2:30 am.

והמבין יבין.

Here are 10 ways to celebrate Pi Day, including this young chap who memorized 2,552 digits (eat your heart out, Brodsky.)

Labels:

Pi

Friday, February 16, 2024

עמודי החצר

In the end of Parshas Terumah, (pesukim 27:9-19), the Torah describes the beams that held up the curtain that surrounded the courtyard of the Mishkan. Pasuk 10 discusses the beams on the southern side of the courtyard:

In Rashi's seemingly innocent comment on the pasuk, there is a grave arithmetic difficulty which is the subject of much discussion amongst the commentators on Rashi. If there are five amos between each beam and 20 beams, that would provide only 19 spaces of five amos. That would yield only 95 of the 100 amos that the pasuk tells us make up the length of the courtyard. Of course, the first notion is that the space does not include the width of the beams. Therefore, there may have been 95 amos of space and five amos of beams to complete the 100 amos. This is in fact the suggestion of the Riva, in the name of his rebbe and is also the opinion of the Abarbanel. The 20 beams on the north and south sides added up to five amos on either side. This would make each beam one quarter amah (1½ tefachim). This interpretation would avoid all our problems from the outset. However, R' Eliyahu Mizrachi takes issue with this interpretation on two accounts. Firstly, he sees no reason why there should be such a large difference between the thickness of the beams of the courtyard and that of the planks of the Mishkan itself (nine tefachim). His second objection is that within the beams themselves you would have some of different thickness than others. On the east and west sides, there are only 10 beams needed to make up five amos. (The nine spaces between the ten beams make up 45 of the 50 amos width of the courtyard.) Therefore, each beam would be three tefachim, twice the width of those on the north and south sides. The lack of symmetry involved in this understanding of Rashi causes the Mizrachi to disregard it and give his own interpretation.

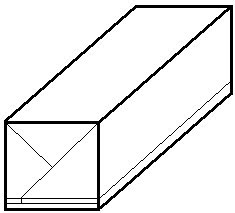

Firstly, the Mizrachi suggests that the five amos referred to by Rashi are not five amos of space but rather five amos from the beginning of one beam to the beginning of the next.. This view is generally accepted amongst all those who deal with this problem with the obvious exception of the aforementioned Riva and Abarbanel. In pasuk 18, the Mizrachi infers from Rashi that the beams were one amah thick. Therefore, the actual space between each beam would be four amos and the thickness of the beam would complete the five amos. However, we have now only accounted for 95 amos. Therefore, the Mizrachi suggests that the north and south sides actually had 21 beams and the east and west had 11 but that the seemingly extra beam on each side belonged to the set of of beams of the side perpendicular to it. For instance, 21 beams were placed on the southern side of the courtyard. The beam in the southwest corner, though, was officially part of the western side. So, too, the beam in the northwest corner was not counted as part of the western beams but as part of the northern beams and so on. See illustration. With this arrangement another space of five amos is added to complete the 100 amos referred to in the pasuk.

In pasuk 18, the Mizrachi suggests that the 100 amah measurement of the courtyard was in fact a measurement from within the beams and the one amah taken up by the beams is not included. This reasoning was given in order to justify Rashi's calculation of 20 amos distance between the Mishkan and the curtains of the courtyard on the north, south and west sides. The Gur Aryeh objects to this with the claim that the pesukim (9,11,12,13) clearly state that the curtains were exactly 100 amos long on the north and south sides and 50 amos long on the east and west sides. But according to the Mizrachi's interpretation, the outer perimeter of the courtyard would be 102 amos by 52 amos. He offers a defence for the Mizrachi that perhaps the only purpose of the curtains was to cover up the open spaces and they did not need to cover the corners (as illustrated on page 3). However, in his own opinion, the Gur Aryeh suggests that the 100 amah measurement is in fact referring to the outer perimeter of the courtyard. He then was required to justify Rashi's measurement in pasuk 18 in a different manner.

The Levush HaOrah, another commentator on Rashi is unhappy with both the Mizrachi and the Gur Aryeh's explanations of Rashi in regards to the placement of the beams. From the fact that Rashi mentions the measurement of five amos between each beam more than just once, he infers that Rashi meant for this to be consistent throughout the entire perimeter of the courtyard. According to the Mizrachi the length of the north side, for instance, was really 102 amos and according to the Gur Aryeh it was 100. However, if you add up 21 beams each of one amah thickness and 20 spaces of four amos each, we are given 101 amos. So, too, on the east and west sides we would end up with 51 amos instead of 50 or 52. He concludes that the only way for the Mizrachi's figures to work out would be to say that one space on each of the four sides was actually one amah bigger. For the Gur Aryeh's figure to work one space would have to be one amah smaller. The Levush does not accept that such a lack of symmetry was present in the building of the Mishkan and offers a rather unique arrangement of the beams. Each of the beams were circular on the bottom for one amah and were inserted into circular holes in the copper sockets that held the beams in place. The beam itself was a semi-cylinder whose diameter was one amah. On each of the corners was placed a quarter-cylinder beam so that the curtain could wrap around it. See illustration. The thickness of this beam was only one half amah on either side. This removes one half amah one either end of each side of the courtyard. With this arrangement, the spaces between all of the beams were all four amos wide without any exception and the perimeter of the courtyard was exactly 100 amos by 50 amos as stated in the pesukim. Amongst all the interpretations mentioned thus far, this is by far the most symmetric and arithmetically accurate.

Finally, the sefer Ma'ase Choshev offers another possible arrangement of the beams which matches that of the Levush's in symmetry and arithmetic correctness. He suggests that there were no beams in the corners. The curtains were suspended from wooden bars. On these bars were placed the hooks that were used to hang the curtains from the beams. Each of these bars was five amos long. The north and south sides had twenty such bars and the east and west sides had ten. These wooden bars would allowed the curtains to change direction at the corners without the need to wrap it around a beam. See illustration. Once again the figure of five amosrefers to the distance from the beginning of one beam to the beginning of the next. With this arrangement the thickness of the beams becomes irrelevant. All of the figures mentioned in the pesukim work out perfectly as well. One advantage of this arrangement over that of the Levush's is that all of the beams are the exact same shape.(The illustration assumes the beams to be one amah thick.)

The arrangement of the Ma'ase Choshev is the one quoted in the seforim Meleches HaMishkan and Tavnis HaMishkan (etc.). The sefer Lifshuto Shel Rashi, however, is content with the opinion of the Riva and the Abarbanel. Whatever the true arrangement of the beams was, it is clear that when Rashi said that there were five amos between each beam, he had some logical calculation in mind. The only question that remains is "Which?".

On a Related Topic

The Mishkan was covered by three layers of material(*). The first covering described by the Torah (26:1-6) was made of twisted linen, turquoise, purple and scarlet wool. The covering was made up of 10 panels of 4x28 amos2. This yields a total area of 40x28 amos2. The Mishkan was 30x10 amos2. The beams that made up the walls of the Mishkan were 1 amah thick. Thus, the Mishkan required 32x12 amos2 of roofing.

The beams were 10 amos tall. The covering was 28 amos wide and 12 amos covered the roof of the Mishkan. That leaves 16 amos for the two sides which is 8 amos on each side. So the wool/linen would reach two amos from the ground. There is a dispute as to whether or not the front beams were covered. We will go with the opinion of the gemara (Shabbos 98b) that they were uncovered as Rashi (26:5) notes that the pesukim seem to indicate as such. Therefore, 31 amos of the covering's width provided roofing, leaving 9 amos to hang from the back. The second covering was a covering of goat hair. This covering was wider and longer than the wool/linen layer and covered it fully on all sides.

Rashi (26:13) notes that the Torah teaches us a lesson that one should show compassion for valuable objects. The twisted linen and assorted wools were very precious and thus, as Rabbeinu Bachya explains, it was made not to drag on the ground so that it would not be soiled by dirt and rain and was protected fully by the goat hair. This lesson is easily understood considering the measurements mentioned thus far. However, there is one simple question to be asked. What about the corners? As the accompanying diagram shows, if a piece of material hangs only 8 amos off one side and 9 amos off the other, simple Pythagorean geometry dictates that the corners will hang down more than 12 amos! (This effect is well demonstrated by the corners of a rectangular tablecloth hanging from the table.)This is hardly an efficient way to care for valuables.

This problem seems far too obvious to have been overlooked by Chazal in teaching us this lesson. However, finding the answer was not easy. But finally, an answer was found in R' Chaim Kunyevsky's elucidation of Braisa diMleches haMishkan. There he asks exactly this question. He answers that the corners of the coverings were folded against the back of the Mishkan as illustrated. The Ritv"a (Shabbos 98b) apparently provides the same answer in the name of Braisa diMleches haMishkan but our versions show no evidence of any such discussion. One of the books on the Mishkan actually show such an arrangement but there is no discussion as to any source or reason for it.

*This and a number of other facts discussed on this page are actually subject to a large-scale dispute between R' Yehudah and R' Nechemiah. For our purposes, all figures are according to R' Yehudah.

Friday, January 26, 2024

חמושים

When B'nei Yisrael leave Mitzrayim, the pasuk says (13:18) that they left "chamushim." Rashi says that the literal meaning is that they left armed. But he brings a Midrash from Mechilta that only 1/5 of B'nei Yisroel came out of Eretz Mitzrayim and the rest died during the plague of darkness because they did not want to leave. In the Mechilta itself there are two other opinions, that 1/50 or 1/500 of B'nei Yisroel came out. This is indeed a disturbing Midrash. It would mean that 2.4 million, or 24 million, or 240 million of B'nei Yisrael died during the plague of darkness. That would make it a far greater blow than everything brought upon the Mitzrim put together. R' Shimon Schwab in Ma'ayan Beis HaSho'eva asks, as well, that the point of the B'nei Yisrael dying during the darkness was so that the Egyptians would not see them dying. It's kind of hard not to notice at least 2.4 million people missing.

R' Schwab answers, therefore, that really only a few people died at that time. The discussion in the Midrash is concerning the long term effects of it and how to gauge it. The first opinion looks only so many generations down the line and sees that at that point, 2.4 million Jews that would have been born never were. The other two opinions simply look farther down the time line to see the greater long term effects of this loss. This would answer all the questions. But what I find very bothersome about this answer is that the wording of the Midrash simply does not seem to lend itself to such interpretation. The number of deaths is not given at all but rather the fraction of B'nei Yisroel that left Eretz Mitzrayim. This fraction would not change over the generations. In other words, let's say 600,000 went out but it could have been 3 million. If generations down the line, we reached a population of 6 million, the projection should dictate that we could have been would be 30 million, still a 1:5 ratio. I don't see how the fraction can be interpreted the way R' Schwab did. Nevertheless, it is the only answer I've seen to these difficulties with the Midrash.

Labels:

בשלח

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)