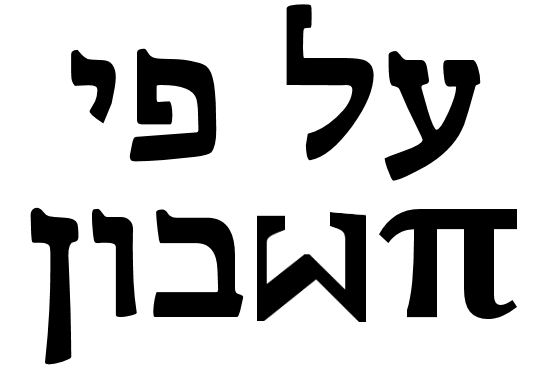

In the end of Parshas Terumah, (pesukim 27:9-19), the Torah describes the beams that held up the curtain that surrounded the courtyard of the Mishkan. Pasuk 10 discusses the beams on the southern side of the courtyard:

In Rashi's seemingly innocent comment on the pasuk, there is a grave arithmetic difficulty which is the subject of much discussion amongst the commentators on Rashi. If there are five amos between each beam and 20 beams, that would provide only 19 spaces of five amos. That would yield only 95 of the 100 amos that the pasuk tells us make up the length of the courtyard. Of course, the first notion is that the space does not include the width of the beams. Therefore, there may have been 95 amos of space and five amos of beams to complete the 100 amos. This is in fact the suggestion of the Riva, in the name of his rebbe and is also the opinion of the Abarbanel. The 20 beams on the north and south sides added up to five amos on either side. This would make each beam one quarter amah (1½ tefachim). This interpretation would avoid all our problems from the outset. However, R' Eliyahu Mizrachi takes issue with this interpretation on two accounts. Firstly, he sees no reason why there should be such a large difference between the thickness of the beams of the courtyard and that of the planks of the Mishkan itself (nine tefachim). His second objection is that within the beams themselves you would have some of different thickness than others. On the east and west sides, there are only 10 beams needed to make up five amos. (The nine spaces between the ten beams make up 45 of the 50 amos width of the courtyard.) Therefore, each beam would be three tefachim, twice the width of those on the north and south sides. The lack of symmetry involved in this understanding of Rashi causes the Mizrachi to disregard it and give his own interpretation.

Firstly, the Mizrachi suggests that the five amos referred to by Rashi are not five amos of space but rather five amos from the beginning of one beam to the beginning of the next.. This view is generally accepted amongst all those who deal with this problem with the obvious exception of the aforementioned Riva and Abarbanel. In pasuk 18, the Mizrachi infers from Rashi that the beams were one amah thick. Therefore, the actual space between each beam would be four amos and the thickness of the beam would complete the five amos. However, we have now only accounted for 95 amos. Therefore, the Mizrachi suggests that the north and south sides actually had 21 beams and the east and west had 11 but that the seemingly extra beam on each side belonged to the set of of beams of the side perpendicular to it. For instance, 21 beams were placed on the southern side of the courtyard. The beam in the southwest corner, though, was officially part of the western side. So, too, the beam in the northwest corner was not counted as part of the western beams but as part of the northern beams and so on. See illustration. With this arrangement another space of five amos is added to complete the 100 amos referred to in the pasuk.

In pasuk 18, the Mizrachi suggests that the 100 amah measurement of the courtyard was in fact a measurement from within the beams and the one amah taken up by the beams is not included. This reasoning was given in order to justify Rashi's calculation of 20 amos distance between the Mishkan and the curtains of the courtyard on the north, south and west sides. The Gur Aryeh objects to this with the claim that the pesukim (9,11,12,13) clearly state that the curtains were exactly 100 amos long on the north and south sides and 50 amos long on the east and west sides. But according to the Mizrachi's interpretation, the outer perimeter of the courtyard would be 102 amos by 52 amos. He offers a defence for the Mizrachi that perhaps the only purpose of the curtains was to cover up the open spaces and they did not need to cover the corners (as illustrated on page 3). However, in his own opinion, the Gur Aryeh suggests that the 100 amah measurement is in fact referring to the outer perimeter of the courtyard. He then was required to justify Rashi's measurement in pasuk 18 in a different manner.

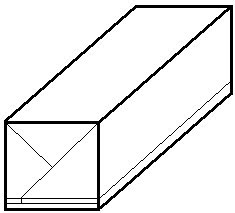

The Levush HaOrah, another commentator on Rashi is unhappy with both the Mizrachi and the Gur Aryeh's explanations of Rashi in regards to the placement of the beams. From the fact that Rashi mentions the measurement of five amos between each beam more than just once, he infers that Rashi meant for this to be consistent throughout the entire perimeter of the courtyard. According to the Mizrachi the length of the north side, for instance, was really 102 amos and according to the Gur Aryeh it was 100. However, if you add up 21 beams each of one amah thickness and 20 spaces of four amos each, we are given 101 amos. So, too, on the east and west sides we would end up with 51 amos instead of 50 or 52. He concludes that the only way for the Mizrachi's figures to work out would be to say that one space on each of the four sides was actually one amah bigger. For the Gur Aryeh's figure to work one space would have to be one amah smaller. The Levush does not accept that such a lack of symmetry was present in the building of the Mishkan and offers a rather unique arrangement of the beams. Each of the beams were circular on the bottom for one amah and were inserted into circular holes in the copper sockets that held the beams in place. The beam itself was a semi-cylinder whose diameter was one amah. On each of the corners was placed a quarter-cylinder beam so that the curtain could wrap around it. See illustration. The thickness of this beam was only one half amah on either side. This removes one half amah one either end of each side of the courtyard. With this arrangement, the spaces between all of the beams were all four amos wide without any exception and the perimeter of the courtyard was exactly 100 amos by 50 amos as stated in the pesukim. Amongst all the interpretations mentioned thus far, this is by far the most symmetric and arithmetically accurate.

Finally, the sefer Ma'ase Choshev offers another possible arrangement of the beams which matches that of the Levush's in symmetry and arithmetic correctness. He suggests that there were no beams in the corners. The curtains were suspended from wooden bars. On these bars were placed the hooks that were used to hang the curtains from the beams. Each of these bars was five amos long. The north and south sides had twenty such bars and the east and west sides had ten. These wooden bars would allowed the curtains to change direction at the corners without the need to wrap it around a beam. See illustration. Once again the figure of five amosrefers to the distance from the beginning of one beam to the beginning of the next. With this arrangement the thickness of the beams becomes irrelevant. All of the figures mentioned in the pesukim work out perfectly as well. One advantage of this arrangement over that of the Levush's is that all of the beams are the exact same shape.(The illustration assumes the beams to be one amah thick.)

The arrangement of the Ma'ase Choshev is the one quoted in the seforim Meleches HaMishkan and Tavnis HaMishkan (etc.). The sefer Lifshuto Shel Rashi, however, is content with the opinion of the Riva and the Abarbanel. Whatever the true arrangement of the beams was, it is clear that when Rashi said that there were five amos between each beam, he had some logical calculation in mind. The only question that remains is "Which?".

On a Related Topic

The Mishkan was covered by three layers of material(*). The first covering described by the Torah (26:1-6) was made of twisted linen, turquoise, purple and scarlet wool. The covering was made up of 10 panels of 4x28 amos2. This yields a total area of 40x28 amos2. The Mishkan was 30x10 amos2. The beams that made up the walls of the Mishkan were 1 amah thick. Thus, the Mishkan required 32x12 amos2 of roofing.

The beams were 10 amos tall. The covering was 28 amos wide and 12 amos covered the roof of the Mishkan. That leaves 16 amos for the two sides which is 8 amos on each side. So the wool/linen would reach two amos from the ground. There is a dispute as to whether or not the front beams were covered. We will go with the opinion of the gemara (Shabbos 98b) that they were uncovered as Rashi (26:5) notes that the pesukim seem to indicate as such. Therefore, 31 amos of the covering's width provided roofing, leaving 9 amos to hang from the back. The second covering was a covering of goat hair. This covering was wider and longer than the wool/linen layer and covered it fully on all sides.

Rashi (26:13) notes that the Torah teaches us a lesson that one should show compassion for valuable objects. The twisted linen and assorted wools were very precious and thus, as Rabbeinu Bachya explains, it was made not to drag on the ground so that it would not be soiled by dirt and rain and was protected fully by the goat hair. This lesson is easily understood considering the measurements mentioned thus far. However, there is one simple question to be asked. What about the corners? As the accompanying diagram shows, if a piece of material hangs only 8 amos off one side and 9 amos off the other, simple Pythagorean geometry dictates that the corners will hang down more than 12 amos! (This effect is well demonstrated by the corners of a rectangular tablecloth hanging from the table.)This is hardly an efficient way to care for valuables.

This problem seems far too obvious to have been overlooked by Chazal in teaching us this lesson. However, finding the answer was not easy. But finally, an answer was found in R' Chaim Kunyevsky's elucidation of Braisa diMleches haMishkan. There he asks exactly this question. He answers that the corners of the coverings were folded against the back of the Mishkan as illustrated. The Ritv"a (Shabbos 98b) apparently provides the same answer in the name of Braisa diMleches haMishkan but our versions show no evidence of any such discussion. One of the books on the Mishkan actually show such an arrangement but there is no discussion as to any source or reason for it.

*This and a number of other facts discussed on this page are actually subject to a large-scale dispute between R' Yehudah and R' Nechemiah. For our purposes, all figures are according to R' Yehudah.